Photographs by Carole Itter

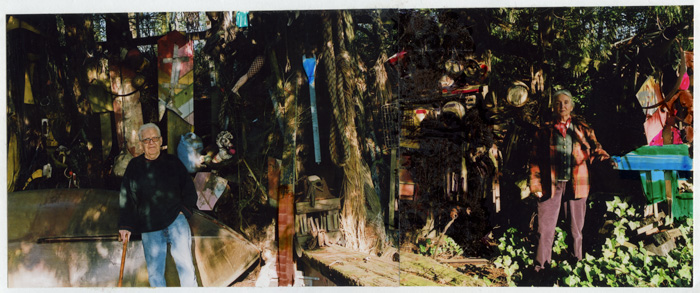

Assemblages at Al and Carole’s Cabin

Glenn Alteen

When Al Neil moved to Dollarton in 1966 he had already had a long career as a jazz pianist and a central figure in the hard bop improvisational scene that flourished in Vancouver in the ‘50s at the Cellar and other venues. He moved out of his place in the West End where he’d lived since the early ‘60s working at the post office and kicking a drug habit. Al’s music was breaking new ground with his three-piece Al Neil Band, and the cabin on the beach at Dollarton gave him a place to escape the city.

There is confusion about the location of Al’s cabin, as it is often misrepresented as the Mudflats, a community that was just beginning around 1966 a couple miles west. But Neil’s cabin was part of an earlier group of squatters’ cabins that had existed from at least the 1920s and was finally razed in the mid ‘50s. This was the squatters community of Malcolm Lowry and other writers and was also a working class community of fisherman, shipbuilders and other maritime trades. Al’s cabin represented the furthest western border of the community that snaked along what is now Cate’s Park, and Malcolm Lowry’s was on the eastern border. Al’s cabin was saved because of its proximity to McKenzie Barge and Shipbuilding, where the cabin’s builder worked starting in 1932. Both squatter communities were on the territory of the Tsleil Waututh, the original people of the inlet with their reserve nearby.

Al rented the cabin for $15 a month from McKenzie Barge. Earlier it had served has a lunch room for the workers at the site and the company ran an extension cord out to the cabin so Al would have power. Later they would dispense with the rent as Al became the watchman for the barge company, taking care of the eastern edge from the rare few people who ventured that far along the foreshore on the tiny path through the woods.

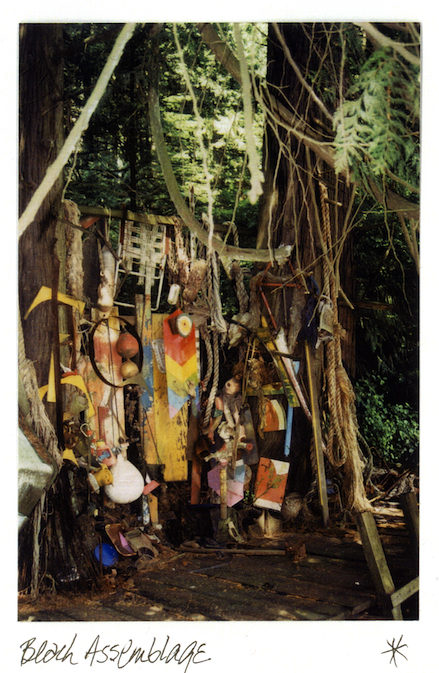

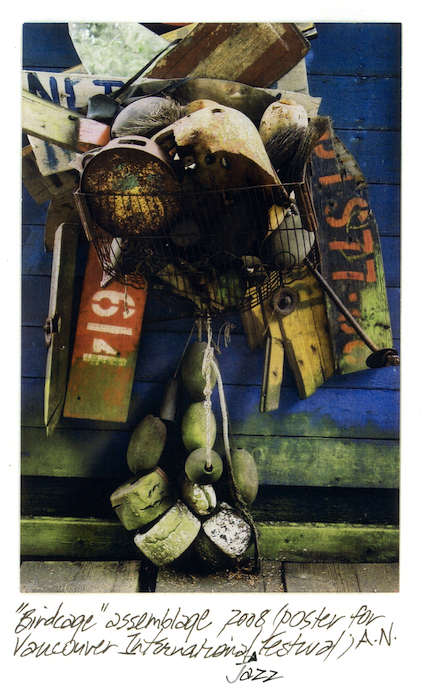

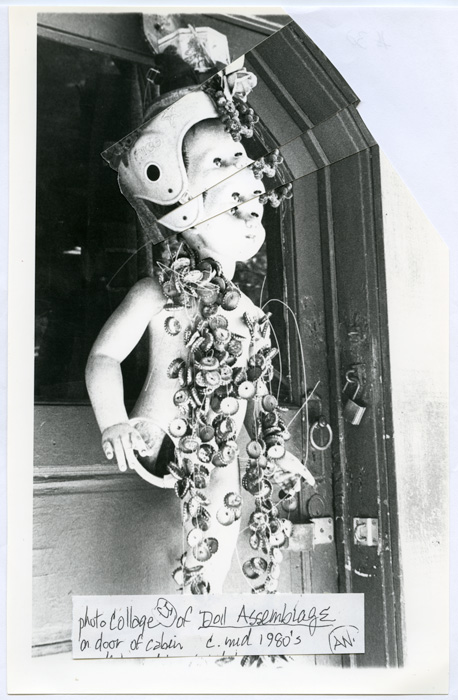

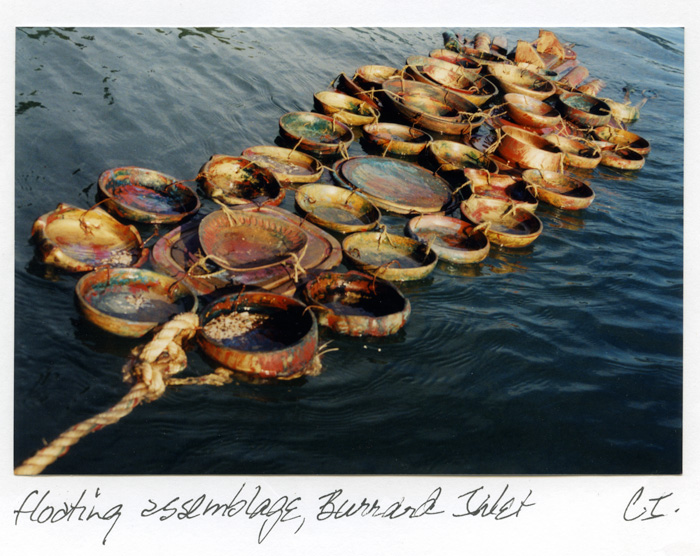

Soon after Al got there, he started building the assemblages at Dollarton, spreading them along the foreshore beside the cabin. He worked at them intermittently, never really finishing them nor meaning to. Rather, they were a constant transforming of the foreshore and often by the foreshore as many of the materials drifted up on the beach as flotsam. The work was flowing and atonal like much of Neil’s music, relying heavily on improvisation and freeform association. Carole Itter remembers visiting him out at Dollarton long before they got together because she was impressed by his work she had seen in photos and wanted to see how it was put together. She was surprised to find out they weren’t attached but leaned against a skeleton support using the weight of the objects to hold them in place.

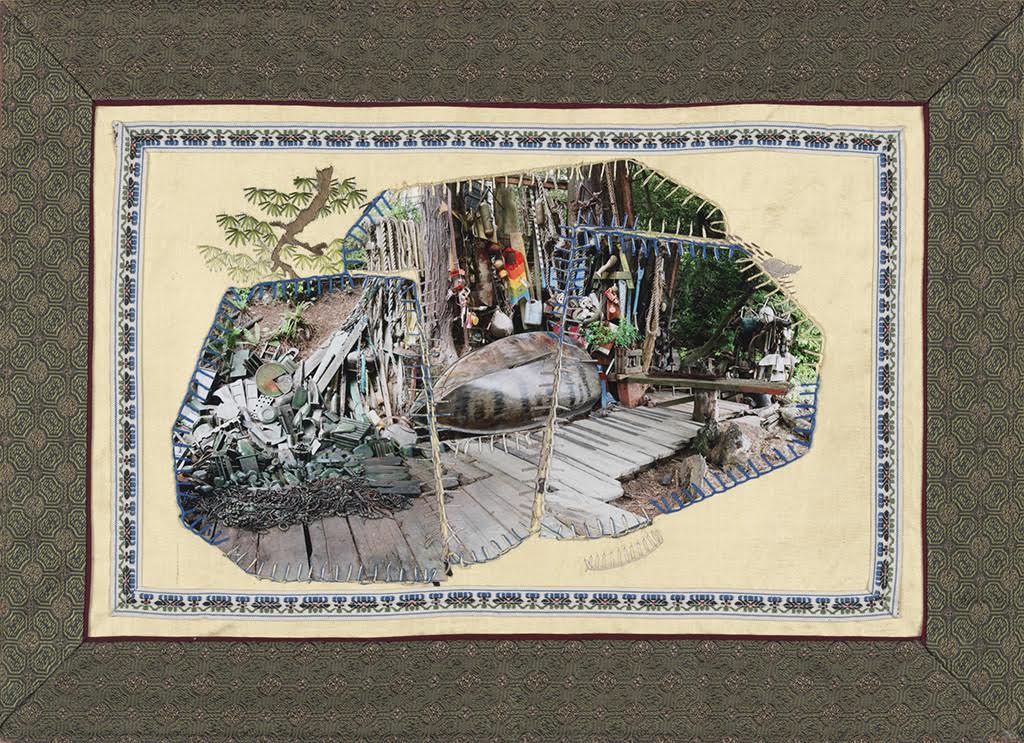

Later, after Carole and Al became a couple, she remembers working with him on the large beach assemblage. Pieces would fall off due to wind or water and because they weren’t attached they could be repurposed elsewhere in the array, and so the assemblage changed and grew. Carole remembers being outside, moving these large pieces as Al stood in the window with his beer and his newspaper gesturing to her to move it one way or the other. The assemblage became an aesthetic negotiation between them over time.

The Blue Cabin was off the grid in more ways than one. Tucked into the foreshore at the western edge of Cate’s Park butting up against the industry of McKenzie Barge, the cabin was hidden in plain sight. Al and Carole did nothing to advertise that they were living there. They understood the precariousness of their lifestyle and what had happened to the other cabins along this stretch of coast and to the Mudflat squats a couple of miles west. They didn’t entertain much. Signage labeled it as a Watchman’s Cabin with appropriate Keep Out, Private Property and No Trespassing warnings. Low profile. Al remembered when he did get an eviction notice from Port Metro in the early 1970s and how Brian McKenzie had talked the Port down and saved the cabin during the time the Mudflats were razed.

Given this situation, the assemblages that Al Neil and Carole Itter created were not for public consumption. They weren’t even created for their friends who in any case were seldom invited there, so never saw them. According to Carole this work wasn’t really being made for anyone; it was all about the making of it. Created by them with the intervention of the tides, the wind and the rain, the piece grew and morphed and changed over the 50 years Al had the residence.

Of course, Al and Carole each had their own art practices in both of which assemblage was central. Al’s work in performance and assemblage installation was established in exhibitions at Intermedia and the Vancouver Art Gallery. Carole says Neil’s sense of the spatial in assemblage was masterful. Working with him on the beach assemblage made her learn to trust Al’s instincts when it came to placing objects. She says it was like a sixth sense.

Al’s practice in visual art came out of his primary career as a bebop jazz pianist, and collage/assemblage was an obvious extension of that practice. Juxtaposition is central to both improvisational jazz and collage/assemblage where emphasis can be on what is missing as much as what is visible or audible. The influence of first generation masters such as Kurt Schwitters and Robert Motherwell was evident in Neil’s assemblage and collage practices. Beginning in assemblage and moving later into collage, Neil’s work was never far from autobiography connected to the writing practice he started in the late 1960s.

Many artists work in a variety of mediums but usually do so in order to say different things or address diverse concerns. Al was unique in that whether working in jazz, writing or collage/assemblage, an identifiable interrelation existed between each of these practices. Stylistically the assemblages and collages related to the bebop improvisation that was his core practice. Thematically they related to autobiographical material Neil wrote in West Coast Lokas, Changes and Slammer. Because of this, there was a continuity between the way he used the different media and the story they told.

Carole’s practice is based principally in installation, though it has often moved into other media such as drawing, painting and collage, sculpture and assemblage, performance art, writing, film and video. Her art evokes our forests and waterways: long hanging rattles or shimmering fabrics that speak so eloquently to natural life here. But her work also addresses these times. Starting as a young artist in the ferment of the 1960s, her work has stayed relevant to the ecological, the feminist, the social and the compelling political concerns of this period. This included conceptual work like the 1972 work Personal Baggage that saw Carole taking a log from the beach on Robert’s Creek on the Sunshine coast, cutting it into sections and transporting it by train to the beach in Lockeport, Nova Scotia where she reconstructed it, documenting and publishing the process in The Log’s Log. As a project it made conceptual links from one coast to another and staked her own personal space inside of this. It was, and always has been, personal to Carole. Her artworks are not disembodied events, but are expressions of her own experiences within the processes of art.

It was after she got together with Neil that Itter started experimenting towards making the large rattle works. They consist of found wooden objects hung on chains, sometimes stained or painted monochromatically, that you can walk through, making the objects move and bang together like rattles or bones. With names like Choir of Rattles, Winter Garden and Western Blue Rampage, these works evoked the majestic West Coast rainforest brought to life through artful low lighting.

They also have a playfulness that is never far away in Itter’s work, a sense of whimsy that sometimes masks her more serious intent if one doesn’t look closely. The objects in these rattles are the recycled wooden detritus of our domestic and industrial worlds. Scavenged and repurposed, these larger objects such as salad bowls and industrial patterns have a presence, if no longer a purpose. In Itter’s work they are put to a whole different employ.

Burrard Inlet became a muse in Itter’s later work—at first the inlet itself through a series of artworks, installations and films such as Fish Film based on the inlet and later the Canada geese that she befriended at the cabin over the years in the ongoing project Inlet. The cabin’s location across the water from the Kinder Morgan Oil Refinery (now Trans Mountain) and the constant tanker traffic remained a constant reminder of how fragile this waterway is.

The Beach assemblage at Dollarton was an amalgamation of both their practices yet at the same time distinct from either. One can see Neil’s sense of design but also Itter’s eye for detail. It was difficult to comprehend at once because no matter how far back you got, your eye would start moving to the details—the little bits and in-betweens. Most of the materials had floated in on the tides and the rest looked like they could have. Itter is a collector with a careful eye as the rattle assemblages attest and the dance the eye does while taking it all in seems carefully choreographed.

That said, the third collaborator here was the weather and tides. Al’s penchant for not tying the pieces together meant that everything was moveable and move it did. The weather wore harshly on the individual elements—be they wood, rope or plastic—and slowly they disintegrated, bit by bit. The weather had less impact on other parts, like Maxine Gadds’s fiberglass boat, and it moved around the assemblage throughout the years, on its side leaning against the assemblage in one photo and upended in another, often changing colour as it changed use. The thick ship’s rope slowly rotted from the rain and saltwater, the wood greying and the plastic becoming pitted as it was reclaimed by the seashore.

To Carole and Al these conditions were part of the project and rather than protect the work from them, they welcomed the intrusion of the elements. From their point of view the weather and sea finished the work and they saw beauty in the deterioration. Later, when the cabin was saved, many people thought the assemblages should be saved as well and there were enquiries to purchase them or parts of them. Neil and Carole wanted none of it. This work wasn’t made to go into a collection. Both artists had produced work that was sold to collectors and museums but this was not the purpose here. There was nothing to buy: some rotten wood and rope and plastic flotsam you couldn’t take into a collection with the salt, beach lice and insects. Plus nothing was attached to anything else, so without Al and Carole the work would be pretty hard to replicate even with all the elements. In the end Al’s assemblages on the side of the cabin were saved but, as a pile of elements, whether they can be put together from photographs has yet to be seen.

The beach assemblages that Al Neil and Carole Itter built at Dollarton were very much a product of that place, that piece of foreshore on Burrard Inlet. The piece of ‘land’ they sat on was old rubble from the shipbuilding industry next door and the wind and water forged the landscape as much as they did their assemblages. Existing in the liminal space of the foreshore with its precarious legal, cultural and physical contradictions, the work took on the same qualities. For the artists the foreshore was a source of research and wonder and it fueled both of their practices in the time they spent there. The assemblages on the foreshore foretold the production both artists undertook as Al moved deeper into collage and Carole began work on her Rattles and later Fish Film and Inlet. And while Al and Carole made their marks on a landscape now disappeared, the landscape left more permanent marks on their work.

May 2020